Key Data Points in Your Vet Hospital’s P&L Statement

- Category: Blogs

- Posted On:

- Written By: Karen Felsted

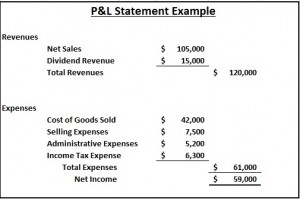

The first question that people ask is: “Why do I need to look at my profit and loss statement?” The answer lies in an old cliché that says “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” While it is easy to ignore clichés because you’ve heard them so many times, these phrases are generally clichés for a reason—they are widely applicable truths that should not be ignored. Obviously these specific words have to be taken with a grain of salt—it’s not necessary to count the paperclips on a daily basis in order to manage the purchase of office supplies but managing most areas of a veterinary hospital well means you need to measure the activities involved. Your veterinary hospital profit and loss statement (aka “income statement” or “P&L”) is a good starting point for revenue and expense analysis.

Revenue

In most hospitals’ P&L statements, revenue is only displayed as a single number called something like “Fees-professional services.” While comparing this figure for a month or year to the prior month or year and calculating the percentage change gives you some idea about the magnitude of revenue growth or decline, the profit and loss statement doesn’t have a whole lot of other information about revenue. In order to analyze revenue more deeply, it’s necessary to look at some of the metrics related to the drivers of revenue—transactions, average transaction charge, revenue by doctor, new client numbers and revenue by category.

Expenses

In comparison, the profit and loss statement is an excellent source of information for expense analysis. You’ll get better insights, however, if the information from the income statement is put into a spreadsheet that allows for comparison of changes over periods of time and allows the expenses to be reviewed as a percentage of gross revenue, not just in absolute dollars.

The key data points on which most of your time should be spent are the high-dollar items–labor costs (both doctors and staff), and drugs and medical supplies expense. However, don’t forget the smaller items–all expenses should be examined in detail at least once a year.

The first comparison to be made for any given expense is between the current period (month, quarter, or year) and the prior period; for example, support staff costs are compared from 2013 to 2014. Expenses that generally fluctuate with revenue changes are better examined by looking at them as a percentage of revenue rather than as a direct dollar comparison. Support staff costs may have declined dollar-wise from one year to the next but if revenue is declining as well, the support staff costs may actually have gone up in proportion to revenue. If you only look at dollar amounts, you won’t see this.

This internal benchmarking is often the easiest kind of analysis to perform because the data is readily available—it’s all internal. However, there is no guarantee that improvement means a practice is doing well; it may simply mean they are doing less badly than before. Some comparison to outside benchmarks is important to make that assessment.

AVMA, AAHA and Advanstar all collect and publish a fair amount of financial and operational metric information that can be used for this kind of comparison purposes. No practice is going to be exactly like the practices included in the study population but this analysis is very beneficial for most practices. For example, if your drugs and medical supplies expense is 17.1% of gross revenue and one of the published studies says this expense is 17% in a typical practice, you aren’t going to get too worried—it’s a minor difference. However, if your expense is 25%, then you should do some investigating. If the majority of practices can keep their drugs and medical supplies expense at 17%, why can’t you? Improving your inventory control could drop a lot of money to the bottom line.

Once you have a handle on which expenses seem high, you need to look at the drivers of those expenses. For example, if your staff compensation looks high, are staff working too many hours? Is there too much overtime? Are they overpaid? Some additional metrics to look at in sorting out the issues are staff hours per transaction and staff hours per day (particularly in comparison to doctor hours/day.) Does this fluctuate per week or month? What can be done to increase efficiency?

Net Income

The last item to discuss is the “net income” figure on the P&L. This is what’s left over after expenses are subtracted from revenue. Perhaps the most important indicator of financial success in a veterinary practice is the true operating profitability. Unfortunately this is the most difficult number to get because it doesn’t show up on any report a practice regularly receives, even when those reports are properly prepared. The net income figure on the P&L is generally a meaningless number and doesn’t represent the operating profit.

Why is net income usually a meaningless number? Net income (i.e. the operating profit) should represent what’s left over after all of the normal and necessary expenses of the veterinary practice are paid at fair market value rates. Often times, not all of the expenses in a veterinary practice P&L statement are “normal and necessary” or they are not “paid at fair market value rates. Some common examples are:

- Practice owner compensation that is not calculated based on the medical/surgical/management work the owner does but instead is just a random amount determined by how much money is in the bank

- Perks (trips to Tahiti, dry cleaning bills, liquor store bills, airplanes, personal lawn service, etc.)—i.e. expenses that are not necessary for the operation of the practice but are paid by the practice in order to gain a tax advantage

- Salaries for family members that are not paid at fair market value rates

- Facility rent that is not representative of fair market value

There are usually 8-12 adjustments that need to be made to an income statement to determine what true operating profit is. You will generally need to get help from someone with veterinary practice financial expertise to know how profitable you are.

The P&L statement is a great source of information for making better management decisions. A monthly review will help you identify problems early on when it’s easier to correct them.